Always Looking – People Who Made A Difference XXVIII

Always Looking – People Who Made A Difference XXVIII

By

John I. Blair

Rev. James Reeb

James Joseph Reeb (1927-March 11, 1965) was a minister, social worker, and civil rights activist. His brutal murder by segregationists while participating in the second Selma to Montgomery march made him one of the martyrs of the American civil rights movement of the 1960s. Born in Wichita, Kansas, he grew up in Kansas and Wyoming as his father followed his job working for an oil drilling tool company. Though he was a sickly boy, he was a good student. During high school in Casper, Wyoming, he also developed his social ideals, which recognized the need to improve the lives of the poor and help those denied their full human rights. As a student he enjoyed football and debate. He joined the ROTC and was soon made its commander. Summers he worked in a filling station or as a laborer at a local air base.

James was a committed Christian. With frequent family moves, he attended churches of various denominations, eventually settling on Presbyterian. “I cannot remember a time,” Reeb wrote, “when I wasn’t in church on Sunday, nor can I remember a time when I haven’t studied the Bible . . . Just before leaving high school I made my decision to enter the ministry.” Reeb joined the Army upon graduation, even though the Second World War was almost over. When he was honorably discharged eighteen months later, in December 1946, his rank was Technical Sergeant, Third Class.

After the army he went back to school, first at Casper Junior College, then St. Olaf College, a Lutheran evangelical school in Northfield, Minnesota. Taking summer courses, he got his A.B. cum laude in June 1950. Later that summer he married Marie Helen Deason from Casper who he had first met at Casper Junior College. They had four children.

In autumn of 1950, Reeb entered Princeton Theological Seminary. He received his B.D. in June 1953 and was ordained at the First Presbyterian Church of Casper. Rather than seek a church, Reeb accepted the position of Chaplain to Hospitals for the Philadelphia Presbyter at the Philadelphia General Hospital. This interest in pastoral counseling had developed during his days at the seminary. In 1955 he earned an S.T.M. in the field of Pastoral Counseling. His experience as a chaplain made him more aware, as his biographer Duncan Howlett pointed out, of “the stark realities of life.”

In high school, Reeb was a traditional Bible-centered Christian; but during college his religious views slowly evolved toward a more liberal understanding of Christianity. He wrote in 1956, “I have clearly progressed in my views until I am much more of a humanist than a deist or theist.” This eventually led him to Unitarianism. A friend had given him Today’s Children and Yesterday’s Heritage by Sophia Fahs. In her book Fahs described the approach she and others followed as they created a modern religious education program for the American Unitarian Association (AUA) during the 1930s and 1940s. Their religious philosophy matched Reeb’s. As a result, after several conferences with Harry Scholefield of the First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia, he resigned his Presbyterian Chaplaincy in March 1957, and contacted the American Unitarian Association about transferring his fellowship from Presbyterian to Unitarian.

During the five years it took to process this request, Reeb took a job where he could work closely with Philadelphia’s poor. He served as youth director of the West Branch Y.M.C.A., 1957-1959. When the Unitarians gave him preliminary fellowship he accepted an offer from All Souls Church, Unitarian, in Washington, D.C. to assist Duncan Howlett, their minister. His primary responsibility was to manage the church’s youth program. His openness, friendliness, and ability to be a mediator were just the characteristics needed in this position. He also worked directly with young people and engaged in pastoral counseling. He was assistant minister from 1959-63; and associate from 1963-64.

|

|

Jim Reeb’s concerns and activities soon moved to the larger community. He supported various Unitarian Universalist groups, including the College Centers Committee, the Greater Washington, D.C. Federation of Liberal Religious Youth, the Board of the Joseph Priestley District and the Middle Atlantic States Ministers' Association. He was just as engaged with organizations seeking to address the social problems of the Washington, D.C., area such as the Interfaith Ministers Group, the Conference on Community Relations, Parents Without Partners, the Committee on Citizen Housing and especially the University Neighborhoods Council.

The one thing Reeb did not do as an assistant minister was preach on a regular basis. He decided he wanted a church of his own in a racially mixed inner city neighborhood where he would be responsible for preaching in addition to counseling, community outreach, and program management. When he could not find a suitable congregation, he accepted the directorship of The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) Metropolitan Boston Low Income Housing Program in 1964. The family moved to Boston, Massachusetts and purchased a house in Roxbury, an area of the city where many African Americans lived. His daughter Anne recalled that her father “was adamant that you could not make a difference for African-Americans while living comfortable in a white community.”

The Reebs joined the Arlington Street Unitarian Universalist Church where Jack Mendelsohn, a social activist, was the minister. Reeb also continued his membership in the Unitarian Universalist Ministers Association and remained in communication with the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA) Department of Ministry. In January, 1965, he joined the UUA Commission on Religion and Race. At the AFSC, Reeb and his staff worked to alleviate the housing problems of the poor by getting the city to enforce its housing code. This eventually led to the creation of the Boston Housing Inspection Department. On the state level, they worked with the American Jewish Congress to enact laws to protect the rights of tenants.

But Reeb's work in Boston was interrupted by national events. On Sunday, March 7, 1965, 500 civil rights marchers in Alabama attempted to walk from Selma to Montgomery and were brutally beaten and gassed by state troopers and local police. On Monday, the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA) in Boston received a telegram from Martin Luther King, Jr., calling for ministers and people of all faiths to come to Selma to support the marchers. By the next day, 45 Unitarian Universalist ministers and 15 UU laypersons had answered King's call and journeyed to Selma. Jim Reeb was one of those who answered.

|

|

On Tuesday afternoon he joined 2,500 marchers for the second march from Selma to Montgomery. Once again, the police stopped them and once again the marchers returned to Browns Chapel A.M.E. Church for speeches, singing and prayers. That evening Reeb had supper with two Unitarian Universalist colleagues, Orloff Miller and Clark Olsen, at Walkers Cafe, a local black restaurant. He had planned to return to Boston that night, but changed his mind. He called his wife to say he was staying one more day. Leaving the cafe to return to Browns Chapel, the trio took a wrong turn and strayed from a black neighborhood into a white neighborhood. Outside the Silver Moon Café four men viciously attacked and beat them. Miller and Olson were wounded while Reeb took a severe blow to his skull from a club. He died two days later.

A memorial service was held in Selma on Monday, March 15. Over one hundred Unitarian Universalist ministers and another one hundred laypersons, as well as the UUA Board of Trustees attended. At the service Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered the eulogy. King said in part: “He was a witness to the truth that men of different races and classes might live, eat, and work together as brothers.”

That evening President Lyndon B. Johnson spoke to a joint session of Congress on behalf of his proposed voting rights act. In his speech he stated that at Selma “long-suffering men and women peacefully protested the denial of their right as Americans. Many of them were brutally assaulted. One good man—a man of God— was killed.” He then urged Congress to outlaw all voting practices that denied or abridged “the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” Despite opposition from some in Congress, and the nation, the landmark act passed and on August 6, 1965, Johnson signed it.

When Reeb had applied for Unitarian ministerial fellowship he wrote, “I want to participate in the continuous creation of a vision that will inspire our people to noble and courageous living. I want to share actively in the adventure of trying to forge the spiritual ties that will bind mankind together in brotherhood and peace.” That he did.

Adapted and abbreviated by John I. Blair from the Article by Alan Seaburg at James Joseph Reeb

Blair adds this personal note: I usually omit details about a subject’s religious affiliation in these bios, but in this case it’s an important part of the story.

Click on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.

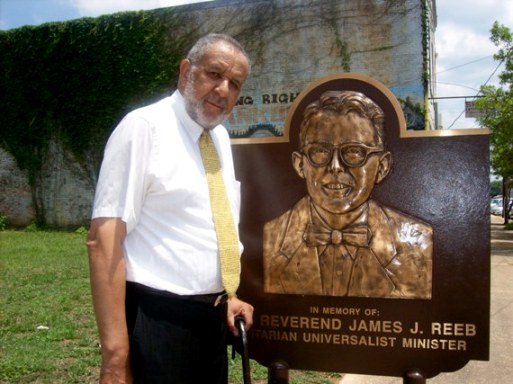

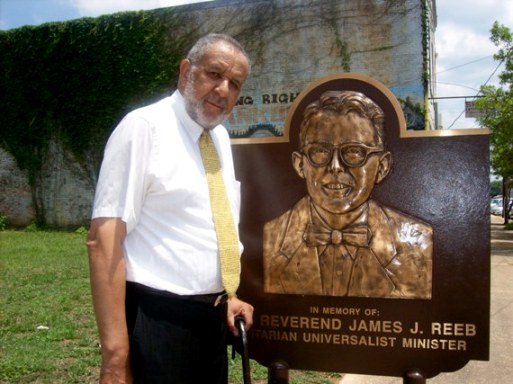

Below:Memorial Plaque

|