|

|

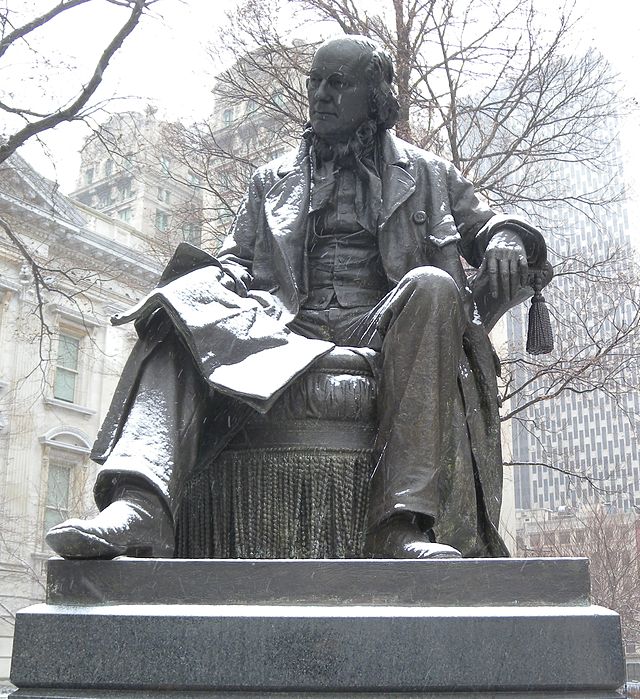

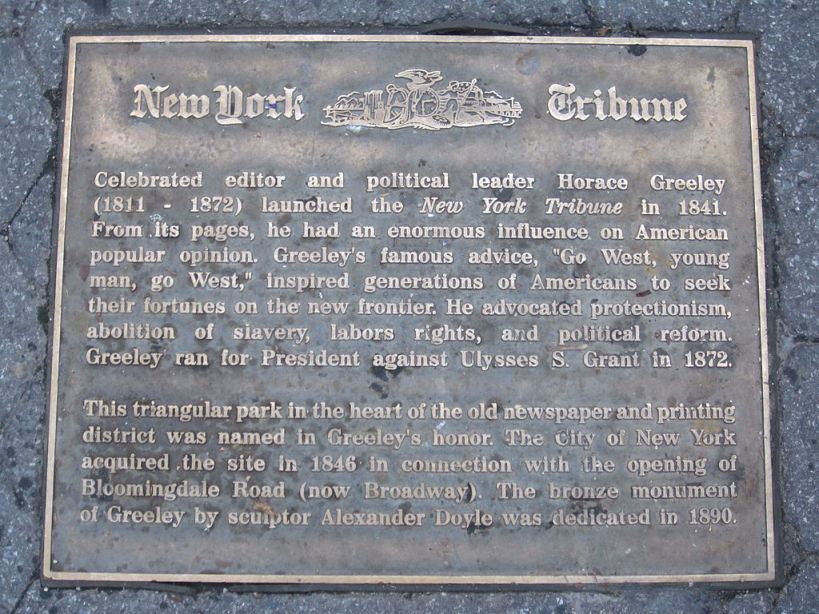

To news reports, Greeley added editorials and commentary on social and political issues, hiring top newspaper men and a few literary stars like Margaret Fuller, George Ripley, and Richard Hildreth. Margaret Fuller wrote reviews and social commentary, later acting as a European correspondent. Greeley taught her to write rapidly and tersely; she lectured him on woman's rights. He was at first skeptical. "So long as she shall consider it dangerous or unbecoming to walk half a mile alone by night—I cannot see how the 'Woman's Rights' theory is ever to be anything more than a logically defensible abstraction." Eventually his opinion shifted. In 1850 he gingerly endorsed the First National Woman's Rights Convention. "However unwise or mistaken the demand, it is but the assertion of a natural right, and as such must be conceded." In the course of his career Greeley came to espouse a wide variety of liberal causes, including abolishing slavery and capital punishment, improving working conditions, and free-soil homesteading. An admirer later wrote, "Greeley labored with the world to better it, to give men moderate wages and wholesome food, and to teach women to earn their living." Greeley was famous for promoting western development and emigration. "If any young man is about to commence in the world," he wrote, "with little in his circumstances to prepossess him in favor of one section above another, we say to him . . . go to the West; there your capacities are sure to be appreciated and your industry and energy rewarded." Greeley helped organize the Republican Party in 1856 and campaigned for Lincoln in 1860. Greeley's political and social views reflected his strongly held religious views, aiming at creating a society in which men and women would be inclined toward actions that "shall ultimately result in universal holiness and consequent happiness." A pacifist, in 1861 Greeley nevertheless came to believe the South had to be resisted with force. He applied public pressure on Lincoln to immediately emancipate slaves. In an 1862 editorial addressed to the President, "The Prayer of Twenty Millions," he wrote that he was "sorely disappointed and deeply pained by the policy you seem to be pursuing with regard to the slaves of rebels." Lincoln famously answered, "If I could save the Union without freeing any slaves, I would do it—if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it—and if I could do it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that." When Lincoln published the Emancipation Proclamation, Greeley rejoiced: "it is the beginning of the new life of the nation." During 1863’s draft riots, a mob nearly succeeded in storming the Tribune building. When weapons were brought in to stave off attack, Greeley exclaimed, "Take 'em away! I don't want to kill anybody!"

Discouraged by the progress of the war and conflicted about use of deadly force, Greeley made several attempts during 1863-64 to bring about peace, each resulting in personal embarrassment. Throughout the war Greeley alternately castigated and lauded Lincoln. "I do not suppose I have any right to complain," Lincoln remarked. "Uncle Horace agrees with me pretty often after all; I reckon he is with us at least four days out of seven." Since his death in 1872, Greeley has been remembered as his country's greatest newspaper editor, an outstanding popular educator, and a notable champion of the downtrodden and dispossessed.

Researched and compiled by John I. BlairClick on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.Pictured below: Horace Greely plaque for establishing New York Tribune.

|