|

|

A turning point came when, during a cholera epidemic in the city, she determined to stay and volunteer her help rather than leaving Daniel and fleeing with her daughters. She quickly developed organizational skills, and when the Civil War broke out she was recruited by Henry Whitney Bellows, head of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, to become coordinator of the Northwestern branch. During the next four years she organized a far-flung volunteer support network for the Union hospitals, visited the hospitals, wrote letters "by the thousands" for soldiers, escorted wounded soldiers from hospitals to their homes, and raised large sums of money in support of the Commission's work.

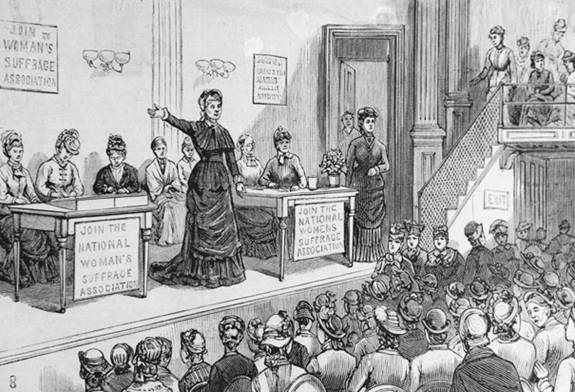

During the war, Mary became "aware that a large portion of the nation's work was badly done, or not done at all, because woman was not recognized as a factor in the political world. . . . [M]en and women should stand shoulder to shoulder, equal before the law." Women, she concluded, needed the right to vote. When the war ended, Mary rose to leadership in the woman suffrage movement, writing and traveling widely as she lectured and chaired meetings. In 1868 she organized the first woman suffrage convention held in Chicago. In 1869 Mary served as editor of the woman's rights periodical, the Agitator. It was not long, however, before she was encouraged to full-time lecturing. For almost a quarter of a century, until her retirement in 1895, Mary devoted herself to this new career, speaking on women's rights and other reform topics "in every part of the country from Maine to Santa Barbara." Her lectures, delivered without manuscript or notes, addressed a wide variety of topics, ranging from women's rights and temperance to immortality. While reflecting her Universalist convictions, all were crafted for broad appeal to a general audience. In "Concerning Husbands and Wives" she held up a model of marriage between equal, complementary partners. In "The Battle of Life" she shared her vision of the better world that was to come and encouraged her listeners to move in its direction. In "Does the Liquor Traffic Pay?" she described the huge social cost of alcohol and called on her audience to join her in winning the temperance battle. In "Has the Night of Death no Morning" she affirmed her belief in the soul's immortality, a belief to be fostered by noble living. In "What shall we do with our Daughters?" she called on her listeners to prepare the next generation of women to take their rightful place in the affairs of the world. The last was delivered more than eight hundred times. Immensely popular as a public speaker, Mary became known as "the Queen of the American Platform." She was the author of two substantial books: My Story of the War, published in 1887, an account of her work with the Sanitary Commission, and The Story of My Life, published in 1897. In 1873, Mary was chosen as the first president of the Association for Advancement of Women. In 1875 she became president of the American Woman Suffrage Association and began her twenty-year presidency of the Massachusetts Woman's Christian Temperance Union. Mary often spoke from Universalist pulpits and at denominational and interdenominational meetings. As a major speaker at the Murray Centennial celebration at Gloucester in 1870, she shared her expectation that "through the doctrines of Universalism" sin will be overcome. Adapted from an Article by Charles A. Howe, All material copyright Unitarian Universalist History and Heritage Society (UUHHS) 1999-2011 http://www25.uua.org/uuhs/duub/articles/livermorefamily.htmlClick on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.Pic Below: Mary Rice Livermore Speaking at Convention

|