|

|

Lydia married Isaac Pinkham in 1843. Like many women of her time, Lydia brewed home remedies. Her remedy for "female complaints" became very popular among her neighbors, to whom she gave it away. Her ingredients were generally consistent with the herbal knowledge available to her at a time when the reputation of the medical profession was low. Medical fees were too expensive for most to afford except in emergencies, and medical remedies more likely to kill than cure. In a day when the mainstream treatment of menopausal conditions was sometimes surgical removal of ovaries — with a mortality rate of 40% — it can be argued that at the very least Pinkham's remedy followed the sound medical principle of "First, do no harm" — a maxim widely ignored by most of the era’s physicians, who prescribed harsh chemicals, including poisonous mercury and lead, and performed rough surgery in septic surroundings. Many preferred to trust unlicensed "root and herb" practitioners and women like Lydia who were prepared to share their domestic remedies. Herbal ingredients, such as Black Cohosh, have been traditionally used by a number of Indian tribes, in Chinese medicine and in western medicine, which gives credence to at least some effectiveness even if double-blind tests were not done to confirm their usefulness. Although scorned by organized medicine, her holistic philosophy predated by a century the “wellness” campaigns of our time.

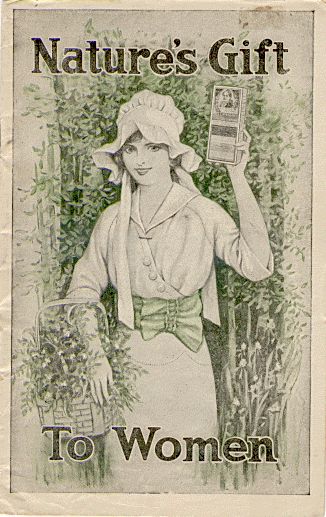

The persistence of Mrs. Pinkham's compound long after her death is testament to its acceptance by women who sought relief from menstrual and menopausal symptoms and to Lydia’s pioneering marketing approach, which made her the first nationally known businesswoman. When her husband was financially ruined in 1873, son Daniel suggested making a family business of her remedy. Lydia first made the compound on her stove, then its success enabled production transfer to a factory. She answered letters from customers and likely wrote most of the advertising copy herself. Mass-marketed from 1876 on, Lydia E. Pinkham's Vegetable Compound became one of the best-known patent medicines of the 19th century. Lydia's true skill was in marketing her product directly to women, probably the first product successfully marketed explicitly to women. She was credited with the company’s slogan “Only a woman can understand a woman’s ills.” Her face was on the label and her company consistently used testimonials from grateful women. Advertising urged women to write to Mrs. Pinkham. They did, and they received answers. She became the Ann Landers of the 19th century. In fact they continued to write and receive answers for decades after Lydia Pinkham's death. These staff-written answers combined forthright talk about women's medical issues, advice and, of course, recommendations for her product. Lydia's famous face appeared on many of her advertisements and trade cards, and she became synonymous with relief of monthly female illnesses.

In the long run, the medicine paved the way for a deeper understanding of women's hormonal fluctuations. Many modern-day feminists admire her for distributing information on menstruation and the "facts of life" and consider her to be a crusader for women's health issues in a day when women were poorly served by the medical establishment. In 1922, Lydia's daughter, Aroline Chase Pinkham Gove, founded the Lydia E. Pinkham Memorial Clinic in Salem, MA. The clinic still operates as a well-baby clinic. Two of Lydia’s sons died of tuberculosis in 1881. The following year she suffered a paralyzing stroke then died during the spring of 1883, at age 64. Her surviving daughter and son continued to be successful with their mother’s famous product, and the company reached a sales peak of $3 million in 1925. In a considerably altered formula, it is still available today. References:www.25.uua.org/uuhs/duub/listoz nwhm.org...lydia-estes-pinkham www.answers.com...lydia-pinkham www.hagley.lib.de.us...lydiapinkhams Click on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.

|