Always Looking--People Who Made A Difference V

Always Looking--People Who Made A Difference V

By

John I. Blair

Meet Roger Nash Baldwin

Born in 1884, Roger Baldwin grew up steeped in a tradition of social responsibility. “Social work began in my mind in the church when I was 10 or 12 years old and I started to do things I thought would help other people.”

In 1981 his memorial service celebrated 97 years of vigorous life. Baldwin had rich, comfortable Boston roots. Relatives included Mayflower Pilgrims and a Revolutionary general. Family friends included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Booker T. Washington.

After Harvard, Baldwin engaged in social work, soon establishing a national reputation. During World War I, he became a leading figure in the American Union Against Militarism. Concerned about safeguarding political rights for conscientious objectors, Baldwin eventually headed the National Civil Liberties Bureau.

First he tried to reach out to top government officials, then he deliberately violated the Selective Service Act. This led to a celebrated trial and his imprisonment. In January 1920 Baldwin helped found the American Civil Liberties Union, which quickly became involved in a series of noteworthy cases, including Sacco and Vanzetti, John T. Scopes, and the Scottsboro Boys. ACLU attorneys helped reshape American constitutional law, concentrating on the protections afforded by the Bill of Rights.

All the while, Baldwin continued to urge Americans to join in fighting fascism, racism and poverty. Revered by many, he also made enemies, including J. Edgar Hoover. Baldwin became increasingly disturbed by purge trials in the Soviet Union and accusations leveled at the ACLU by the House Committee on Un-American Activities. After the Nazi-Soviet pact of August 1939, he worried for the very existence of the ACLU. The following spring, Baldwin campaigned to revise the ACLU charter so those affiliated with totalitarianism could not serve on its Board.

At the same time, Baldwin and the ACLU challenged internment of Japanese-Americans and Japanese aliens. He continued to fight such violations of civil liberties, while seeking to stay on good terms with the federal government. In 1947 General Douglas MacArthur called him as a civil liberties consultant in Japan.

In late 1949, when Baldwin resigned as ACLU director, Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, "You have done wonderful work with the Civil Liberties Union. More than any other agency in this country, it has kept alive the traditional rights of man." Margaret Sanger declared, "The name Roger Baldwin and Civil Liberties are synonymous in the minds of all people in the United States."

For the next several years, Baldwin worked for international human rights. His book, A New Slavery, condemned "the inhuman communist police state tyranny, forced labor." In South Vietnam he criticized the repressive regime of Ngo Dinh Diem. By contrast, in Puerto Rico, Baldwin remained close to Governor Luis Munoz Marin, a former fiery socialist; jailed independence leader Pedro Albizu Campos; and cellist Pablo Casals, among others.

In India, Baldwin maintained a friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru and his family. As the 1960s began, Baldwin worked at the United Nations as a consultant for the International League for the Rights of Man.

He was praised for his support of civil rights for black Americans. In a moving tribute, Margorie M. Bitker referred to Baldwin as "long the moving spirit of the American Civil Liberties Union . . . a pacifist, the only label, by the way, that he is willing to wear." Bitker quoted him as affirming, "The rule of law in place of force, always basic to my thinking, now takes on a new relevance in a world where, if war is to go, only law can replace it."

Adapted from an article by Robert C. Cottrell at

www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/unitarians/baldwin_r.html

Click on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.

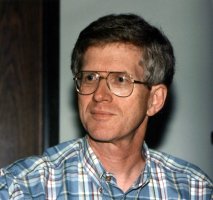

Baldwin, middle aged and at his most active period of his life.

|