Always Looking –It’s Complicated!

Always Looking –It’s Complicated!

By

John I. Blair

Always Looking – It’s Complicated!

Do you remember the old comic song “I’m My Own Grandpa”? It was a big hit as sung by Ray Stevens (and others) in the 1950s.

Many, many years ago when I was just twenty-three,

I was married to a widow, she was pretty as could be.

This widow had a grown-up daughter who had hair of red

And my father fell in love with her. Soon they too were wed.

This made my dad my son-in-law--changed my very life!

My daughter was my mother because she was my father's wife!

To complicate the matter even though it brought me joy,

I soon became the father of a bouncing baby boy.

My little baby he then became a brother-in-law to Dad.

Well, that made him my uncle--made me very sad!

Because if he was my uncle then he also was a brother

To the widow's grown-up daughter, who, of course, was my stepmother.

My father's wife then had a son who kept them on the run.

And, of course, he became my grandchild because he was my daughter's son.

My wife is now my mother's mother and this makes me blue

Because although she is my wife, she's my grandmother too!

Now if my wife is my grandmother, well, then I am her grandchild,

And every time that I think about this, it nearly drives me wild!

Because now I have become the strangest case that you ever saw

As husband of my grandmother, I’m my own grandpa!

And the chorus after every verse is, of course:

I'm my own grandpa! I'm my own grandpa!

It sounds funny, I know, but it really is so!

Oh, I'm my own grandpa!

(Lyrics Copyright Colgems-EMI Music, Inc.)

Now when I was a kid, listening to, and laughing at, this song, I thought it was just a funny song. But then, years later, when I “got into” genealogy and the history of my family, I began to wonder . . . .

The first thing you have to consider is how much sparser the population was, even 100 years ago, let alone 200, 300, 400. Outside a few cities, most people lived scattered across the countryside on farms and ranches, just a few per square mile. On the frontier, they were even fewer and farther apart – sometimes just a few hundred in a “county” that might be several thousand square miles back in the 1700s.

And it’s hard to picture today in an age of high-speed freeways, trains, airplanes, just how hard it was to travel, even as far as the nearest town (if there was one), in the “good old days”. Far from having highways, there weren’t even roads as we know them – just rough trails through the forest in the East or muddy tracks across the prairie in the West. And it was dangerous – wild animals, bridgeless streams, hostile natives. People stayed close to home.

The consequence? A boy or girl growing up scarcely knew anybody else who wasn’t blood kin or close to it. Communities often consisted of several interrelated families who grew ever more interrelated through repeatedly marrying off their children to each other – not necessarily to cement alliances (though that could be a factor) but just because that was the only option unless an eligible stranger showed up on the doorstop at the right time. Think Dogpatch (if you remember that) without the bare feet and corncob pipes (maybe).

One of the problems many genealogists run into, researching so-called Old American family lines (i.e., families who’ve been here since before the Revolution) is the confusion of similar, and even identical, names. Just for one of many examples, in my mother’s family in the 19th century there were three cousins named Richard Rowe Veale, from three different lines, all sharing the same grandparents who were named Richard Veale and Temperance Rowe. To tell one Richard Rowe Veale from another in family histories, you have to footnote their parenthood. (And location – one lived in Texas, one in California, one in Missouri.)

Now part of that stems from the grand old custom, still honored in some families, of naming children after ancestors/older relatives. I, for example, am named for my two grandfathers. My brother for a grandfather and a great uncle. And my son was named for his two grandfathers. Nice, but it really produces confusion for genealogists. I have a couple of family lines who I occasionally will swear only used a dozen given names in 100 years.

But another part stems from the intermarrying. It occurs in any frontier society for the reasons I’ve outlined. Lots of places it was hard to find a potential marriage partner who wasn’t a cousin of some degree or other. Partly because of this, it was not until after the American Civil War that a trend started to discourage marriage between cousins – a trend that ultimately led to many states actually banning it (most recently, Texas, in 2005).

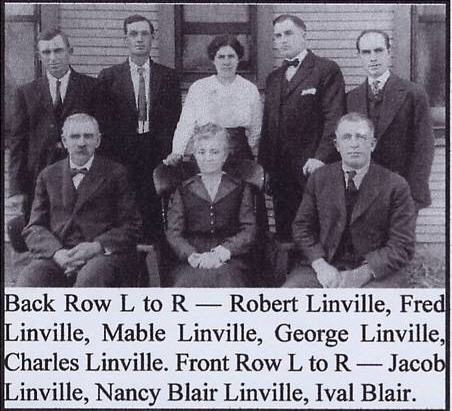

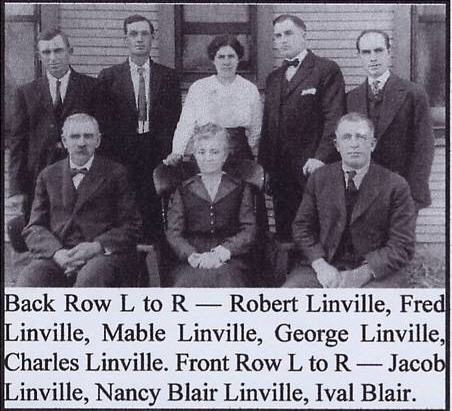

And even with avoidance of marriage between cousins, there were, and are, many other possibilities that avoid consanguinity but embrace confusion. Of all the many examples in my own family, one stands above all others. My great grandfather, Andrew Franklin Blair, was the son of Thompson Milton Blair and Sarah Elizabeth Linville. (The Blairs of our line are of unknown background except they were “from Kentucky”; the Linvilles are part of a clan that pioneered beginning in Pennsylvania and Virginia and continuing through North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, and on west.) Frank Blair served briefly as a teenage soldier in the Civil War, then in 1869 married Nancy Matthews McWilliams – daughter of another pioneering family from Missouri. They had one son, Ival Melville Blair, in 1870. Then, in 1874, Frank died of an illness thought to have been brought on by hardships he suffered during his military service. He left Nancy a widow with a small child, living in rural western Iowa, at least partly dependent on the kindness of her in-laws for support.

In the same area, a young man named Jacob Linville, a second cousin to Andrew Franklin Blair through his mother’s family, was also having a rough time. His first wife, Minta Lawson, whom he’d wed in 1873 not long before Nancy Blair became a widow, died just a couple of years after their marriage, childless. He remarried to Aquilla “Quilla” Woodrum in 1878 and this time had two children with her, Fred and Mabel. Then, in 1882, Quilla died, leaving Jake with two small children. Almost inevitably the two bereaved parents gravitated toward each other in that rural community in Mills County. Likely they knew each other from attending the same country church, the center of social life, such as it was. In 1884, they married, then sold their possessions in Iowa and moved to start a new life in central Nebraska. There they had three more children, all boys.

So now my grandfather Ival Blair was stepson to his father’s second cousin, making him and Fred Linville both third cousins and step brothers. And in Nebraska the two of them met and grew fond of a pair of lively sisters, Grace and Lee Herring, and married them. Now they were not only third cousins and step brothers; they were also brothers-in-law!

|

It took me years to sort that all out. Linville Family pictured. |

In the little cemetery in Mills County, Iowa, where my great-great grandfather and great-grandfather Blair are buried, perhaps half the cemetery is occupied by the Blair, Linville, Estes, Delavan, Allison, and Utterback families. They all lived on neighboring prairie farms; they all attended one or the other of a pair of country churches. They all intermarried with each other. Just a cozy family grouping. The Estes and Blair families had even traveled to Iowa together in covered wagons back in the early 1850s. And now, 160 years later, I’m on Facebook with a couple of Estes and Delavan descendants, making the circle complete again in a tiny way.

So nowadays, when I think of the old song with which I began this column, I have a slightly different reaction. I still laugh, or at least grin; but no longer think of it as being totally beyond belief. I have begun to sympathize with the singer, just a bit.

©2010 John I. Blair

Click on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.

|