Irish Eyes

Irish Eyes

By

Mattie Lennon

Tales of Ballydrum, etc.

John Edward Henry (1904-1986) was a native of Ballydrum, Swinford, County Mayo. He emigrated to the USA in his mid- twenties and spent a number of years in Chicago before returning to Mayo in 1931. When he came back, he married his childhood sweetheart, Margaret Salmon and took over the running of his family farm in Ballydrum.

He also worked with Mayo County Council as a supervisor on road and bridge construction for a number of years. The nature of his work meant that he was often absent from home from Monday morning to Friday night for weeks on end.

It was during those periods of enforced absence from home and family, that he gathered much of the stories and anecdotes that would later form the basis of his folktale collection.

He used to invite older members of the community to chat with him about the customs and habits of their own times and those of previous generations, which he felt were in danger of being discarded in the name of progress. Very few others of his time felt the same desire to record and preserve for posterity the folk heritage of previous generation that was in danger of being lost forever but this did not deter him in the slightest.

John Henry or “Sean” as he was also known left a collection of stories about everything from “Barnala Wood” to “Bellmen.” Whether it’s an account of the “Big Wind” or a Connaught person’s take on “Ninety-Eight” the true storyteller is evident.

When Sean was a young lad a certain “Knight-of-the-road”, who was better dressed and seemed to be on a slightly higher mental plain than the average tramp, used visit the area.

He was known as “the Toff” and when he told a story young Henry hung on every word

and would, decades later, commit it to paper

“ . . . In my great grandfather’s time,” said The Toff, “there were little few glass windows to be found except in the Big Houses, and churches and with some well off people here and there. Among the poorer people, there were various excuses for windows. In some houses, long, narrow openings in the walls served for windows. It was narrower on the inside than the outside and a board was fitted on the outside at night or in bad weather. In some cases, a mare’s placenta or a sheepskin with all the wool and fat removed was stretched across the ‘window.’

These allowed a dull light to get through but were far from being as satisfactory as glass. A good many dwellings then were only ‘bohauns’ or mud huts; they had no light except what came in over the half door.”

“My great grandfather was known locally as Mairtín Bradach. (Mischievous Martin) He went to Sligo on one occasion and brought back a pane of glass. He was so careful of the glass that he carried it all the way home on his back in a sack that was well-padded with rags and paper. He never once sat down on his journey of 22 miles. With the help of a local handyman, he fitted the glass to a wooden frame and installed it with the proud boast that it was the first glass window ever to come to the village of Cruck.”

The Toff went on to add that his great grandfather had a well-known habit of turning things around when he spoke. So, when a neighbour who came across him while fitting the window, asked him what he was dong, he received an unexpected answer.

“I’m tying to let out the dark,” my great grandfather is said to have replied.

“Letting out the dark, as Mairtín Bradach said,” became a popular saying in the locality afterwards.

When the window had been fitted, some of the neighbours felt it that a celebration known as a ball was called for. Accordingly, a small money collection was held and Mairtín donated the food and the music, he being a player on the fife or wooden flute.

During the ball, Mairtín saw a neighbour to whom he had not spoken to for some years, peeping in through the new window. There were two lighted candles, one on each side of the window, and he had no trouble recognising the ‘gobadán’ (curlew) as this man was known locally. He had a very long nose, which earned him his title.

After making up his mind, Mairtín moved quietly to the back door and picked up the hardest sod of turf he could find. Moving stealthily, he waited until he got beside the window. He waited until the gobadán had his long nose right up to the window. Then he let fly catching his opponent full on the nose and of course breaking the window in the process.

Sean amassed a considerable pile of wire bound notebooks and jotters as he went about his labour of love and in later years he used those notes to write his folktales.

A number of those stories were published in book form by the Mercier Press (Cork) in the late seventies under the title of “Tales from the West of Ireland.” This book was re-issued in 2000 and both editions were quickly sold out.

He contributed to a number of periodicals and magazines and for a long number of years he wrote articles on contemporary Irish social and economic affairs for an American travel company’s newsletter.

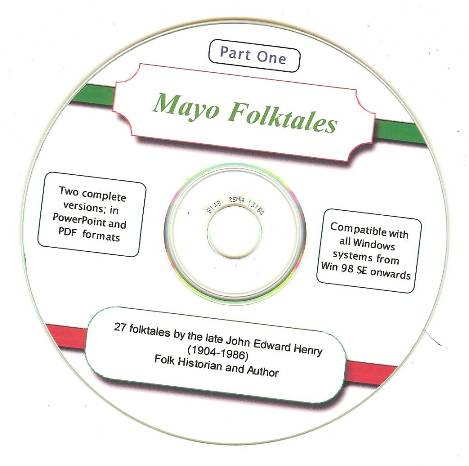

“Mayo Folktales” is a collection of his stories that have been published in digital from by his son, Eamonn.

There is a total of 54 articles in this collection and it had been arranged in two volumes for distribution purposes.

Both volumes are available on CD-ROM as well as in PDF format for direct downloading from the site; www.mayotales.com

The CD versions are designed to run on all Windows operating systems from Win 98 SE onwards and as PDF is a cross-platform format, those files are compatible with all common computer platforms and are not limited to Windows’ users only.

Full details may be had from www.mayotales.com

The CDs cost €10 each or €15 for both excluding postage costs. The PDF documents are priced at €7 each or €12 for both.

Click on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.

|