|

|

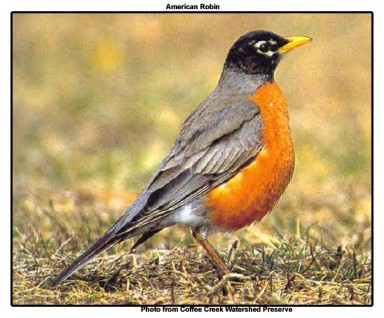

At first it was through eyes virtually blinded by ignorance. I could barely tell the difference between a robin and a redbird. Nonetheless I knew how much I loved watching the redbirds – cardinals – hop to pick up seeds, watching robins stalk earthworms and pull them patiently from their burrows. How much I loved listening to the robins sing their springtime triplets from the television antennas on every house in our block, to the cardinals tink-tinking through piles of scattered autumn leaves.

As I grew a bit older I greatly enjoyed taking drives through the countryside with my Dad, or with my Uncle Ralph in his rattling old farm truck, looking for hawks and crows, and for crows chasing hawks (and owls), learning lore about what they hunted, how they affected rural lives. I found that both Uncle Ralph and Dad knew a lot about birds, things they’d learned growing up in the country, from their own parents, grandparents, uncles (and aunts). And that both were open to coping with revelations that some of what they’d learned as boys was not necessarily correct. I still remember the day my Uncle Ralph told me he’d changed from being ready to shoot all the hawks and owls he could to believing they needed to be protected because they got so much of their food by hunting and eating rats and mice. (See pic of Cooper's Hawk at bottom of column.) And Dad (who was, after all, a college graduate) started reading books about birds so he could give better talks to the Scout groups he worked with, learning along the way far more than he’d ever known from oral folklore. Stuff about why birds migrated, where they went, and how that was important to other parts of human life. About where they nested, and how humans could help them find nesting sites by building bird boxes. By the time I was twelve I’d built (with Dad’s able assistance) a couple of wren boxes, and seen birds raise nestlings in them. I’d hand fed, then successfully released, a juvenile bluejay, rescued when its parents died. Now that’s involvement! The hassles of adolescence and college years distracted me from doing much birdwatching for a long time; but then I had the joy of teaching my New York bred wife, then my son, some of the stuff I’d been blessed with by Dad and Uncle Ralph. We bonded over birds. For several decades now my wife and I have maintained a bird sanctuary in our urban yard. No pesticides; a supply of fresh water; bins of nourishing birdseed kept filled 12 months of the year, rain or shine, summer or snowfall. Many generations of finches and cardinals and doves have been raised on the strength of the provender we put out. I think of them as “our birds,” rather species centrically. They may just as well think of us as “their people.” All through the day, every day, all we have to do is look out the kitchen window, or the patio door, and see dozens, sometimes scores, of birds, feeding, drinking, sunning themselves, flying about, mating, even nesting, sharing their lives with us without stint.

Birdfeeder Karma Take care before

Unless you aspire to be

And when one winter day ©2003 John I. Blair Birds continually offer all of us an extraordinary, precious opportunity to watch, up close, other species living out their lives, and even to (very carefully, and only with sufficient knowledge about how to do it without harming them) interact with their lives. Almost all other types of animals rightly shun humans; birds just go on with business. These little dinosaurs (for that’s what science tells us they are) adapt with ease to a world created by us humans. They’ve been here many millions of years longer than us, after all. If you aren’t already in love with watching them, give it a try. One word of advice – with gulls and pigeons, don’t park your car too close, and wear a hat. Click on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.Below: Cooper's Hawk

|